Some Theological Reflections on Christ and COVID-19

Why Did It Happen?

Like you, I have seen a number of different theological comments about COVID-19. Why did it happen? Why did God allow it to happen? What sort of answer might Christians have to this crisis? Perhaps also like you, I have not found any of the theological reflections particularly satisfying. People seem to be operating out of their already-existing theological grids—their “agenda,” if we wish to be blunt—and wheeling out that set of categories and applying them to this situation.

Think Differently

That approach is certainly understandable; we all tend to think along certain fixed lines, and as we get older, our minds naturally default to particular grooves of thinking. But while understandable, it is not good enough. I think of the famous Einstein comment that the thinking level that got us into a problem is not going to be a sufficient level of thinking to get us out of the problem. We need to think differently (or as Steve Jobs would say, “think different”) to solve the problems facing us.

COVID-19 is forcing us to think more clearly along at least three lines: our theodicy, our ecclesiology, and our theology proper.

Our Theodicy

Theodicy is the attempt to explain suffering. Surely, we have a new set of challenges here: A virus that strikes without mercy at the most vulnerable. People dying alone without family or friends. No platitude will suffice. We must dig deep to find a way of thinking about this that is intellectually satisfying, but also authentically genuine at the emotive level.

Our Ecclesiology

Similarly, the virus and the resulting lockdown are forcing us to think more clearly about our ecclesiology, the doctrine of the church. Church is by its very nature a gathering. What can we do about a gathering ministry when we cannot gather?

Our Theology

But perhaps most striking of all, we are being forced to think more clearly about theology itself. What does this virus say about our understanding of God? What kind of God is this that would allow this sort of thing to happen? Has our understanding of God in the past been too enamored with the sentimentality of pop evangelicalism that it did not sufficiently drink from the wells of God’s suffering people globally, as well as across history?

Christocentric

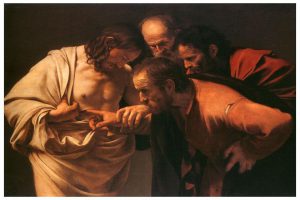

The answer—and yes, I do think there is an answer—lies in the face of Christ. The Old Testament answer to suffering is all gathered up in that extraordinary book called Job. But the New Testament goes further. While the Old Testament grapples with the meaning of life (in the Book of Ecclesiastes) and the meaning of suffering (in the Book of Job), the New Testament proclaims the mystery has been revealed in the death and resurrection of Jesus.

To think differently, we need to shift away from the rampant mere moralism of most of contemporary Christianity and move towards a more rigorously Christocentric message in terms of the practical functionality of church life and the Christian life. So many messages that are given today from the pulpit, as well as in songs, have basically been a Christianized version of insightful practical advice for how do well by doing good. COVID-19 destroys that cozy moralistic and deistic consensus. When I am facing death, hearing three (or more) tips for how to have a happy marriage is not a sufficient answer. It feels trite. It feels inadequate. It is all those things and more.

The Puritans and Suffering

I spent many years delving into the historical theology of the Puritans and in particular Jonathan Edwards. Looking from that vantage point—and those Puritans knew a thing or two about suffering—the strange celebrity-obsessed deistic moralism of much of so-called evangelicalism today is astonishing. It’s time to think differently. To think better. To preach better, too.

In the well-known Christian classic The Rare Jewel of Christian Contentment, Jeremiah Burroughs has a paragraph on what we need to learn from plague. Plague had ravaged seventeenth century London, and the sermon in this famous book was preached in the context of one of those plagues. Listen to what Burroughs says:

“I see a family in which all was well only a week ago, and now everything is down, the plague has swept away a great many of them, and the rest are left in sadness and mourning. We see there is no resting in the things of this world, yet the Lord has made with me an everlasting covenant ordered in all things. I find disorder in my heart, in my family; but the everlasting covenant is ordered in all things, yes, and it is sure.”

An Eternal Perspective

That’s the different kind of thinking we need to rediscover today. An eternal perspective. A confidence not in this present world but in the promise of God (his “covenant”) found in Christ, his death and resurrection, for those who repent and believe in him. That covenant is reliable: “yes, and it is sure.”

None of that is simplistic or implies easy answers to real pain and the darkness of Job-like experiences of suffering. We do not live in the “best of all possible worlds,” the simplistic answer to suffering that Voltaire so mercilessly lampooned in Candide. We live in a world where a man can be crucified. Where the God-man was crucified. We may not live in hell, but anyone who has read about (or visited the remnants of) concentration camps where so many millions were butchered cannot doubt that at times this world feels like hell. Indeed, there are the seeds of hell here—right in each of our human hearts and in the broken world all around us. There is certainly much to lament. But, as Christians, we do not live on Good Friday. We live in the hope of Easter Sunday. There is a resurrection to come.

Christ’s Victory

In Christ’s resurrection is proclaimed hope of victory even over COVID-19. “Where, O death, is your victory? Where, O death, is your sting?” Or as the prophet Hosea puts it (from which the apostle Paul quotes those famous words in 1 Corinthians 15), “Where, O death, are your plagues?” Even the plague, even COVID-19, has heard its defeat announced in the victory of Jesus over death at the empty tomb.